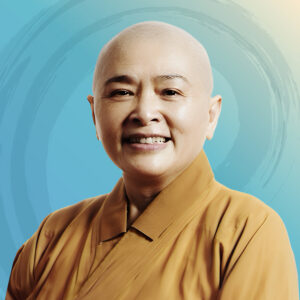

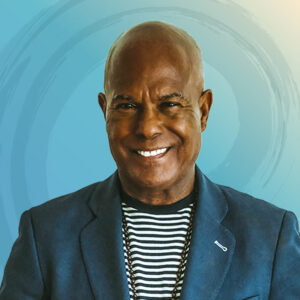

Thomas Hubl: Hello, and welcome everyone. My name is Thomas Hübl and I’m the initiator of this Collective Trauma Summit 2020. And I’m delighted to sit here with Sharon Salzberg. Welcome, Sharon. Welcome here in the summit this year.

Sharon Salzberg: Thank you so much.

Thomas: So, of course before our conversation, I looked more deeply into your work, and actually there are many aspects, first of all, that I feel deeply resonant with, given your deep spiritual background, that’s very close to my heart anyway. But also the applications of the spiritual practice in our society, spirituality and activism, spirituality, and social architecture.

And in our case here during this summit, we are exploring from many, many different angles, artistic angles, scientific angles, psychotherapy angles and many more, how we actually approach a phenomenon that is with us for maybe hundreds of thousands of years. People got traumatized, people got healed, people got more resilient, and all of this is kind of cyclic patterns that come back again and again.

And I would love to explore with you how the practice of mindfulness, or also, maybe also deep commitment to mindfulness, which I think is also a question in itself, what does it mean to be deeply committed to mindfulness? And it starts for me always with, since meditation is with you for most of your life,how did meditation meet you? And let’s start there, a little bit about your personal journey, how you found that pearl in your life, that is the main river of your giving and sharing and teaching? Maybe, you can start there and then we take it a little bit deep into the trauma world.

Sharon: Sure. I was just reflecting this morning that I started meditation practice moving on toward 50 years ago. So, it really has been the greater amount of my life. And how did those numbers happen? How did they accrue? It’s ridiculous and mystifying and amazing and all of that.

I grew up in New York City and I went to college in Buffalo, New York. And it was when I was in college in my sophomore year, I took an Asian philosophy course and it was really, I think looking back, almost happenstance. I looked at the schedule, I thought, “Oh, that’s on Tuesday, that’s convenient. Let me do that one.” And it changed my life in a couple of different ways. One was in talking about the Buddhist perspective on life, where the instructor said the Buddhist talked about life having suffering in it, that this is an inevitable and natural part of life.

I, like many people that had a very disrupted traumatic childhood, figured out by the time I went to college, which was at the age of 16, I’ve lived in five different family configurations, each of which had ended because somebody died or something truly terrible had happened. And like many people, my family system was one where you didn’t ever talk about it. And so, I didn’t know what to do with all of those feelings inside of me, the grief and the anger and the anguish and so on. Here was the Buddhists saying, right out loud, in effect, “You’re not so different. You belong anyway. You’re not so weird. You don’t have to feel so isolated with this pain.” So, that was the first thing.

And then I heard, in the context of that class, there was such a thing as meditation practice, that there were methods that were actually direct and very pragmatic methods you could use, if you were interested, that would help you be happier. So, if I was going to describe myself at that age, which was 18-years old, in one word, I would say “fragmented”. I felt fragmented. And I heard that meditation, maybe, held the promise of weaving me together in some way so I felt whole.

I looked around Buffalo, New York, this is 1970, I didn’t see it anywhere. So, the university had an independent study program. And if you created a project that they liked, you could go off, theoretically, for a year, and then come back. So, I created a project, I said, “I want to go to India and study meditation.” And they said, “Okay.” And off I went.

Thomas: Lovely. That’s lovely. So, just to stay with the biography for a moment, and then you went to India and what happened there for you?

Sharon: Well, I was very much interested in that sort of direct pragmatic approach. I wasn’t very interested in the philosophy or comparative religion, or didn’t want a new identity and didn’t want a belief system. And it took me a few months to find just that. And I did find just that, which was in the context of this intensive 10-day meditation retreat led by S.N. Goenka in Bodh Gaya, India. And that was January 7th, 1971, is when it began. And I never looked back from that. I’ve used a lot of different methods or I’ve explored a lot of different approaches, and very grateful for that. But from that first night of the first retreat, I just felt there’s truth here for me, there’s healing here for me, and I never looked back from that.

Thomas: Oh, wow. Actually, that’s the year that I was born.

Sharon: Oh yeah. Hey, you are as old as my meditation practice.

Thomas: Yeah, that’s right. So, fantastic. And circling back to one word that you said is, fragmented. And in the understanding of trauma, we talk a lot about the fragmentation in the nervous system. The fragmentation, as I see trauma as a systemic kind of fact, that we see the fragmentation in our societies and cultures, and often we approach the symptoms of the fragmentation and not the root of the fragmentation.

And so, since you brought this in by yourself, now, how do you see that the meditation practice supported you to maybe heal or kind of bring that fragmentation back into a kind of a more unified inner world? So, I’m interested with, how did you experience that over the years?

Sharon: Yeah. I mean, I’m still using it. I’m using it in our times right now, very much so. So, I think about that a lot. What’s sustaining me, what’s supporting me, what’s helping me in times of anxiety and distress and chaos. And it’s really, it’s the same tools in so many ways.

There are lots of different aspects to the meditation practice. The first we call concentration, it’s really about cohering, it’s bringing together and integrating these different experiences. And it’s also establishing a place of rest where the chaos may be happening internally or externally, but we have a refuge. We have a place of rest, that could be the breath. It could be something else happening in your body. Some neutral place where you can just kind of chill and watch everything that’s going on rather than being enmeshed in it or pulverized by it.

And so, that was very important as a tool for me. It also involves gathering your energy, which for everybody is kind of scattered, usually. We’re distracted, we’re all over the place, we dwell in unhealthy way in the past, or anticipate in an unhealthy way the future. And it’s a process of bringing our energy together, kind of having a place to land.

And then I use the meditation … One of its great skills is teaching how to be with painful feeling, a heartache, a heartbreak, fear, agony, all those things, in a better way. So, we’re not adding shame and dread and this effort to be in control of what we can’t control, but to approach those feelings with compassion for ourselves. And that’s a whole learning. Most of us were not born with that skill or raised even with that skill.And so, it was very important for me.

And then there’s a lot in the meditative process about allowing the joy, being with the beautiful feelings and the wondrous experiences, which we might be too distracted to notice or too ashamed of. There’s so much suffering, how can I possibly allow myself to brighten up for a moment? Or something like that. And so that was a whole learning.

And then, very profoundly, I have found meditation to be a process of deep connection, not only to myself, but to life, to others. And I think it’s the weirdest thing because on the face of it, you might be all alone with your eyes closed. It looks the most cutoff activity you can imagine. But the truth is, it brings us deeply in touch with how connected we all are. So, I learned that January 7th of 1971 and I’m using it, believe me, really a lot right now.

Thomas: Right. Yeah, we’ll come back to right now in a second. And so, you said something beautiful that I want to, maybe, highlight or underline, that it’s a way to create kind of inner coherence and inner presence, but it’s also a way to feel more connected. And in the way we understand trauma is that, through trauma, the circuits that connect inside and outside are fragmented, so that’s why we feel separate. We feel isolated, we feel alone. And what I heard from you is that meditation actually supported your experience to unify the inner world and the outer world in you, again. Would you say that that’s how you experienced that?

Sharon: Yeah, I mean, I certainly didn’t have the sophistication to understand the effect on my nervous system, for example, but it didn’t take that long to discern that there was a big cultural message I had taken in and I think it can be very prevalent for some people. The message that if you’re frightened, if you feel overwhelmed, it’s something you should be ashamed of, that we need to get in control of everything or at least something. And you’re not making it somehow because you can’t.

And so, on top of all the distress and whatever the primary effect is, we can easily add that sense of stigma or shame or, “I need to hide this.” And I think that reflects on how we look at others. If someone is in trouble, someone is distressed, it’s like, “Let’s just put them away somewhere, so we don’t have to see it. I don’t want to look at that. They must have caused it because they lost control.” And I think it’s a big message that we get.

Thomas: Right, absolutely. Maybe you can speak to this more in depth. In the way we do healing and integration work of trauma, we say that everything a child—mostly children—does in order to protect him or herself is an intelligent function and not a weakness, even if in a grownup life, it looks a weakness. So, bringing in a self-compassionate way or more understanding that actually the things we suffer from were our childhood heroes, as I call them often. So, to contract and to hold the fear is very intelligent for a 2-year-old girl or boy.

And then, when later on in life we feel shy or we feel kind of disconnected and alone, it looks like it’s a problem, but it’s actually an intelligent function that needs to be understood on the level of its development. And I’m wondering … so, that self-compassion or a different way to relate to myself and be curious about the processes in myself, I think, is a deep aspect of healing. And I think it needs also a cultural framing, that that’s how we look at ourselves. And so, I would love to hear your thoughts on that because I think it’s an important aspect.

Sharon: Yeah. I mean, I think that’s very beautiful. It’s understanding the strategy was very wise for a 2-year-old or an 8-year-old and maybe not so useful right now as the singular way we approach a problem or a painful situation. And with all due respect, dissociation is not a bad idea sometimes and it could be okay, really. But you don’t want to be stuck in just the kind of repetitive, singular approach to life, and it’s time, as an adult, we have the power of awareness. We have the power of recreating our perspective. We have the power of compassion that maybe was not available to us much earlier. And so I think that is a big part of the healing and certainly what one can experience in meditation.

I think it almost comes in the order, within meditation, with first the development of self-compassion, then the ability to look at all the traits or habits one might have, in a kinder way. And it’s difficult for people. I’ve taught self-compassion for so many years and so often somebody will equate it with laziness or just giving in or submitting to something, saying, “It’s all right, let it be.” And it’s really not that at all.

It’s actually a powerful engine in order to make change because the most sustained kind of change is not going to come from a harsh punitive environment, internally or externally. So, it actually is a kind of courage to say, “Okay, I’m going to try this approach and see what it’s like when I can actually have some kindness towards myself.”

Thomas: Yeah, very powerful. I love it that it actually takes courage to be able to soften back into the places that we have to leave in ourselves. And it’s much easier to hover on top of them and be more tight and more strict. That’s lovely, like a softening. You speak beautifully also about love and real love. And maybe you want to share with us your understanding of love? Or maybe your inner development of your own capacity to love? And also how love is actually one of the change factors and also being a social architect? And then maybe we can transition a bit to the social dimension.

Sharon: Yeah. Well, when I think of love, I think of, within the Buddhist tradition, it’s called Metta, M-E-T-T-A, two Ts. And it really, most profoundly means a sense of connection. It doesn’t mean liking somebody or approving of them or giving in to them or anything that. It’s a profound knowing that our lives are intertwined, that the construct of self and other and us and them, which is useful, is a construct. And that there’s a kind of ‘we that is really a very fundamental truth, of the truth of interconnection.

And so, when I think of love, I think of this inner capacity to deeply know that connection, it may or may not be emotional. It may or may not result in, “Let’s spend time together, let’s hang out together.” It may not involve a reconciliation with somebody who’s really harmful, for example, but within, we’re free.

One of my favorite definitions of love, actually, came from a movie called “Dan in Real Life”, which was some years ago, where one of the characters says, “Love is not a feeling, it’s an ability.” And I love that because it reflected so many of my deepest experiences in meditation, where I realized that when I thought of love as a particular feeling, it was a commodity. And it was in someone else’s hands to give me or to take away from me.

I kept getting the image of the delivery person standing at my doorstep, holding the package and looking down, glancing down at the address and saying, “No, it’s the wrong address.” And I’m like, “Wait a minute.” Then I have no love in my life. Then I’m bereft. Whereas, if it’s an ability, if it’s a capacity, it’s within me, and other people certainly may ignite it or threaten it, but it’s mine to tend, to be responsible for, to interject.

I thought, “Well, if it’s my responsibility and I want to have love and a conversation, maybe I have to be the one to bring it in.” And if I want it in the room, maybe I have to be the one to introduce it. And so, I really do think of it as this capacity. And it’s not in any way a weakness or sickly sweet. I think it’s really our superpower to connect that fully.

Thomas: That’s lovely. It’s on one of superpowers. That’s beautiful. And what you said also about the interconnectedness, it reminds me of, I often say: when I look at you, Sharon, then I see you already in me. When often people say, “Let’s keep a professional distance,” or for doctors or healthcare workers, the patient is out there. Yeah, but the patient, once I see the patient and feel the patient, the patient happens in my nervous system. So, it doesn’t get any closer than that.

And I think, how we navigate in our world within that intimacy that’s anyway there, that I can contract, that I can numb, that I can dissociate from, but if those are my tools and not awareness-based tools, then as a healthcare worker, where especially in a cultural crisis now, through COVID or through climate change, we actually can just kind of disembody ourselves or contract more,versus what I heard you saying is you develop an ability to more and more embrace that in ourselves. That’s very powerful.

And I’m wondering, since I know that you work, also, a lot with people that work on the front lines of, now, the healthcare system or activism in the world; I mean, I’m currently living in Israel, and so I have seen people coming to Israel and trying to be activists or making peace and then be burned out and frustrated. And because it’s kind of a hardship if we approach it in a certain way.

And I wonder how you experience this and how maybe your teachings can support people. Because many people that listen to this summit will be in one way or the other people that are active in the world. And also dealing often with traumatizing or traumatized situations, people. I would love you to speak a little bit to them.

Sharon: Sure. Well, I got mostly involved or certainly most profoundly involved with people caring for other people, people really on the front lines of suffering, through the Garrison Institute. They began a program which I was a part of for about four years, bringing tools of yoga and meditation and kind of community building to frontline, domestic violence shelter workers, people who were working in the shelters and then ultimately directors and supervisors of shelters. And then that program morphed to international humanitarian aid workers.

We did that for a number of years and at this point, because of everything happening, it’s kind of coming awake, again, in the States, domestically. And I learned so much from those people on so many different levels about resilience and about compassion and so on.

So, one of the things that came forth very quickly with the domestic violence shelter workers was this notion of establishing a culture of wellness at work, that was their term. And the culture might mean your body and mind. It might mean your desk. It might mean your team. It might mean your shelter. It might mean your classroom, it might mean your hospital, whatever it is. And there were different elements to that.

One woman, interestingly enough, and this speaks a lot to what a lot of people who are in the caregiving professions face, she said, “I’ve decided that in order to help establish a culture of wellness at work, I’m going to start taking a lunch break.” And everyone in the room who did not work in a shelter, was aghast. We said, “You don’t take a lunch break?” And she said, “There’s too much suffering. There’s too many crises. There’s so much need, but I’ve realized I can’t go on unless I build in that break.” And so, because we were meeting regularly, we got to hear her progress.

And the first time she came in, she said, “It didn’t work. I closed the door and somebody crouched down and looked through the keyhole and they saw that I was in there. So, I didn’t get a break.” And then, maybe three weeks later, she came back and she said, “It worked. I closed the door and turned off the lights and I got a break.” So, I kept thinking that most significant moment in that whole story was probably her realizing she needed it. And she was going to go for it. That resilience does not happen without a kind of self -care that’s not selfish or self-preoccupied. That was part of what was very clear.

Also, many people had tools of resilience. Going out in nature, listening to music. And some of them, this is a completely true story. We would have people write down, “What do you usually do to get a break, to get perspective, to have renewal?” And then in another column, we’d say, “Is there anything you want to say about what you’ve just written down?” Somebody wrote down, “I get out in nature.” And then they wrote down, “I haven’t done it in seven years.” That is a completely true story. So, helping people get back in touch with the tools that they do have already and encouraging them.

It’s okay. It’s not self-centered because the work is so hard and dealing with systems that aren’t changing all that quickly. And all the attendant distress and frustration and the need to be patient, all of that, it’s very difficult. And yet the human to human effect is so important. It’s so really significant in that helping people find the inner strength, the respite, even just the realization that this is hard. I had read once, maybe you can help me remember who said it. Somebody said that trauma or traumatic response is a normal reaction to an abnormal situation.

Thomas: Right, yeah.

Sharon: And so, I think, normalizing people’s feelings of distress and exhaustion and meaninglessness, it’s not because they’re weak or not up to the job. It’s so natural.

Thomas: Right. It’s beautiful what you said, because, as you said, in the understanding of trauma, I look at trauma, like the trauma response, when somebody has an overwhelming experience, what happens within us is something that we learned over a very long period of time to protect ourselves, to survive better. The response in itself is very intelligent, but the aftereffects are often severe if it’s not being integrated. And I see what you teach, mindfulness and presence and meditation and all the spiritual practices that help us to get more integrated as one remedy.

And I see the relational aspect; relation in community as another remedy. And I’m wondering because when we look at, and I would love to hear your thoughts on that because … I think collective mindfulness or collective presencing is one remedy for collective trauma. And when I say that, I would love to hear what are your thoughts on that. How the community aspect, the sangha aspect, the aspect that we are practicing together, that we create spaces where we come together and there’s also relational mindfulness, relational presence, maybe you can expand a little on that.

Sharon: I think even within the Garrison program, there were different aspects of it. One was the yoga or mindful movement. One was the meditation practice, both mindfulness and loving kindness. One was a kind of psychosocial understanding, which itself I think was very helpful for people to realize, “This is my nervous system. This is not my personal weakness. There’s a science behind this, why I’m feeling the way I am. It’s not because I’m not up to the job.”

And another part, the fourth part was community building. Because even though, say, in those particular examples, people were all in the same profession, pretty much, they didn’t feel comfortable talking to one another or being with one another. And they all said, “I can’t bring this home. I can’t talk about this at home.”

Not just for confidentiality reasons, but it’s too terrible. I can’t burden my partner or somebody with this kind of story. And so, not talking to one another, not talking to anyone else, it just became like this pressure cooker. And just these community building exercises … These are people you can trust and you can reveal vulnerability with and it’s okay.

And they will also, and we can learn to listen and not feel, “I’ve got to give a perfect response. I’ve got to fix this and make this better.” It’s just being together in the space helped everyone have that sense of, “Okay, here we are. Let’s start here and just witness what we are going through together.” And it was very, very important. I think it has a lot to do with, even before COVID and this crisis, people were talking about an epidemic of loneliness in a lot of places around the globe. That sense of disconnection can be so strong and it’s really important to address.

Thomas: And so, when you look at, I mean, you started to mention this now as well, is like there’s COVID, there’s the epidemic of loneliness, there is a looming climate change catastrophe with maybe millions and millions of people being climate refugees and the natural disasters. And so, there’s a whole list of possible new collective trauma dissertations. When in fact, we didn’t yet really integrate racism, slavery, the Holocaust, like many, many other layers of collective trauma that are sitting within our bodies throughout generations.

And so, when you look through your lens at the world of today, and maybe that’s also in your new book, maybe, how do you look at, from your lens and with your practice and with your background, at the world of today? What concerns you? What kind of possibilities do you see? Maybe you can talk a bit to them.

Sharon: Well, it all concerns me. I mean, I try not to dwell in anticipation. It’s hard enough perhaps, for many people right now. I’m also inspired by people I’ve met, say, in the gun violence community in the States, people who’ve been affected, often tragically, by gun violence. And there are people who maybe have lost a child due to gun violence and so on. And what they talk about is love, really. Love over hatred.

Or look for the helpers, which is a famous quote from Mr. Rogers, this is a television hero who said, “Look for the helpers. When things are falling apart, look for the helpers.” There are heroes in every community who are not famous, who are stepping out and joining in with people, feeding people, taking a stand with a bereaved family, recognizing that on top of whatever painful situation one is in or traumatic situation one is in, reinforcing the idea of loneliness, of aloneness, “You’re on your own, too bad,” that’s the worst thing ever.

And so, even if we can’t make the initial problem just resolve, as much as we would like to, that horrible corrosive feeling of being so unseen, so uncared about, that we can address. When I was writing the book, I got to interview many activists and frontline people, some of whom had a meditation practice, some of whom did not, but everybody was expressing an understanding that the presence of one’s being and caring was the most important thing. And we’ll see what solutions may emerge from that.

I just see it again and again, and I’m really inspired by that. When I just focus on the terrible, terrible things, I realize all kind of those people I was talking about, the caregivers who feel, “I can’t let in the joy, it’s too selfish.” I go, “Oops, I’m doing it too.” That’s not really that good. It’s better to have a more balanced perspective.

Thomas: Yeah. So, I want to highlight what you’re saying. I think that, especially … I call all the caregivers and all the medical system and all the people that work on racial justice, these are the firewalls of the society that absorb a lot of trauma. And I think it’s kind of the immune system of the society over the global immune system, all those systems around the world that deal with traumatization and suffering and disease and mental disease.

I think it’s very important what you say, and I want to highlight this, that we need to be nourished in order to do the job sustainably because being exposed to trauma every day, as you said … I listened to—because I work a lot on the Holocaust past and second World War in Europe and how it’s connected to Israel and Israel, Palestine—some of the stories of survivors of concentration camps, I mean, they’re simply heartbreaking when you listen to them. It’s unbelievable what some people survive and in which way they continued living the life after that.

And so, some people really, it’s like magic how you can survive a catastrophe like that and then still afterwards build a life that works and is successful. I think that your message of everybody living the joy and recharging the battery and knowing how to do this is a crucial factor in being a sustainable immune system and not one that gets drained. And if you want to share more about that and or your experience of how we can take care of ourselves when we work a lot with trauma or with difficult suffering circumstances.

Sharon: Well, I think it is such a crucial point. I was also reflecting just the other day, how I grew up in a Jewish family raised by my grandparents, ultimately in New York City. And I heard all those stories of the Holocaust from such and such cousin is coming to stay for a while. They’re a little crazy, but that’s because they were hiding under the bed when their parents were killed or something that. And I was just reflecting what a sort of extreme situation I was exposed to as a child, because those were the family stories.

And it was like, wow. That is almost beyond belief that people survive and even raise children in love and not in hatred, which is actually a testament in the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C. The last thing is this sort of video presentation from survivors before you exit, and that was the last thing I heard. This woman who’d been a child in the Holocaust and lost her parents, and the last thing she said was, “I raised my children to love and not to hate.” And I walked out the door and I was like, “Wow!”

So, part of it is realizing, I think, it’s okay to take care of yourself or to care for yourself. It’s not easy to come to that realization. It feels there’s so much pressure. There’s so much suffering. We are also taught we need to fix it. We need to kind of master the situation and make it all better, rather than feeling, “Okay, I am present and will see what can emerge from that.”

So, addressing that I think is an important thing, and then I’d go back to that list when I said, “List the things that you have done. Listen to music, look at art, talk to a friend, take a walk, look at the sky, whatever it is. And remember, you can do these things, that they will nourish you, they will help you.” And then of course, for me, I would suggest if you’re interested, “You can add tools of meditation,” things like that. That is not so esoteric or abstract, it’s something that can really nourish your ability to be aware and to be balanced and to foster that deep sense of connection.

Thomas: And now, moving a little bit to the deeper aspect of the spiritual practice. There’s often the discussion that says … There are some people that are deeply involved in the world that say, “Hey, listen, I mean, you’re sitting around, the house is burning, and you’re with yourself all the time, and it’s kind of an escape. It’s kind of a bypass.”

And so, where is it true, maybe, that we use spiritual practice as a bypass not to meet the challenges in our life. So, to try to go to other levels in ourselves, but not to stay with whatever is really painful or problematic or hard, and try to get away from that and kind of run away from our karma. Or in a way, make it our deepest ally in meeting the world. I’m sure you heard this many times throughout your decades of teaching, this kind of, where is the middle path where our spiritual practice becomes actually like a deep well of resource and connectedness to meet challenges in our world. And maybe you can speak a little to the bypass and to the resource.

Sharon: Yeah. I mean, I think it’s a great way of describing it as the middle way, because there are actually two extremes that I see, and I’d be very interested in hearing what you see in your work.

One extreme is people being over heroic. Like, “I’m going to break through this, I’m going to transcend this. I’m going to sit with this pain until I fall over because that’s the way,” and it’s not the way. Suffering itself is not considered redemptive. It’s not what is onward leading. It’s the balance, the presence, the love, the compassion we can bring to the suffering that is transforming. And so, I see that extreme a lot. I’m not going to sleep. I’m not going to give myself a break. That, I think, just needs to be mentioned.

And the other extreme is exactly what you described, “I think I’ll just not look at this at all.” And just have that—somewhere, someday—that mix of bliss and peace that will be totally elevating and will last forever. I mean, you may get that moment, but it’s not going to last forever anyway. People, of course, do that a lot. It’s very tempting to just avoid the painful reality that one might be carrying.

Some of it, I think, is understanding that there’s a middle way and that neither extreme actually serves you. And some of it is just witnessing, “Neither extreme serves me. That I’m just in Lala land,” if you’re going in that direction. And there’s that missing of actual human connection, because if you can’t acknowledge your own pain, you’re not going to be able to acknowledge the pain of others. And herein lies a lot of loneliness and lost connection. And so some of it, I think, is actually that realization.

And some of it, I think, is just encouragement. We don’t necessarily have many models of people who integrate that inner work and outer expression, but we have some. And to find them, they might be very not famous people in your community, who are coming from a place of real deep knowing that our lives have something to do with one another, that you can’t go it alone. That’s not the truth of life. And they respect the people that they work with and work for, and it’s very genuine. And I think if we find those models, it’s very encouraging.

I was talking to the head of a medical practice not too long ago in this hospital. And he said, “You know, I have this really big new appreciation for, it’s the cleaning staff.” Think about that, the people we take for granted, that we look through, that we discount ordinarily. What happens if we stop and we look at them instead of through them? And you think, “Well, I don’t really want to be a surgeon in this hospital when the cleaning staff is not doing their job.” Really, we depend on a lot of people.

Thomas: Yeah, that’s beautiful, that interdependence of everything, I think COVID shows us this very vividly around the world. And I want to ask you, because now that when I listened to you, I thought it’s interesting to see, or to hear about your experience, because in the meditation practice, when we look at trauma and contemplative practices, we could say, on the one hand, meditation is very beneficial as a resource to bring presence, love, love and kindness, compassion to our traumatizations and use it as a resource.

And sometimes, especially in longer retreats, it happens also that people kind of get stuck in dissociated spaces and then hang out in the stagnation in a kind of a not feeling state, in a kind of a dissociated state. So, they are not anymore connected to their energy, but they are kind of in the … and that’s kind of a stuck place.

And so, when you meet this in your practices that you lead,what can anybody who is listening now, or when people touch very early attachment traumatization, then the meditation can get really hard and people stay in loops in themselves. So, maybe you can speak a little bit to that from your experience, what the practitioner can do or not do? What’s a good guidance here?

Sharon: Well, I think it’s, first of all, important to remember that the forms that we experiment with in terms of a meditation practice are simply forms. We tend to get attached to them as the only way, like an intensive silent retreat. Maybe it’s not that smart at this point in your life.

I tell the story in my book about a soldier who came back from active duty in Iraq, and he came to the Insight Meditation Society, which if he had asked me, it would have been the last thing I would have recommended, “I think an intensive silent retreat where no one is making eye contact is good for you right now, two weeks.” No! But he came anyway. And so, we did a kind of parallel retreat for him, which didn’t involve silence and didn’t involve intensive sitting. But people get attached to the form and they think, “Well, I’m being given remedial work.” Take a walk or serve somebody else, help somebody out. So, it’s not remedial work.

If you think that goal is balance, which is what it is, balanced doesn’t mean mediocrity. It really means a kind of spacious ability to hold everything. Balance is going to look different for different people. For some people, it means step up, get engaged. Other people, it’s like, “Whoa, you can step back.” That would be a much better state.

And so, trying to lay out the framework for that, I think, is very important, so people don’t start judging themselves as being inferior because they’re being guided in some way to take a walk or something like that. And also, I think we have both a different understanding of the nervous system and science, and then, it might have been, cite a case from me practicing in an Asian monastery long ago.

And that’s wonderful because it means there are many more resources of energetic … in terms of dealing with the nervous system, different disciplines, qigong, yoga, acupuncture. And then the therapy. The old-fashioned way, like my experience, was a very personal relationship with a teacher, many teachers over time, who work quite personally with people. Like, “Try harder,” or, “Stop meditating.” I mean, I’ve heard all kinds of things suggested, “Just relax.”

And that’s not the case very much anymore because we are practicing in the abstract with an app or in a large crowd. And so, in a way, each person has the opportunity to fill in the gaps, whether that’s a therapist or counselor or a group, or study or movement. And I think we need to look at a path as something very broad, which has all of these elements in it.

Thomas: Beautiful. When you look at the path, I love to say that one of the traps in the meditation practice is, like as a junior practitioner often we look at the end of the path, we’re looking at the end, the forward projection of our own mortality onto the spiritual path, so it has to end somewhere. Versus, I think, from a certain level of experience as a practitioner, we start being on the path really, and walking the path.

And maybe because sometimes I believe it’s looking at how … I will practice hard when I run a marathon, but then I’ll go on to get there. And then I’ll be at the end and it will just be blissful. And it’s like one of the big illusions, which I see also is an avoidance of some trauma, maybe, that led to it, being present and being here is hard. So, it’s easier to look at there. And so, maybe you can speak to that. And then I have one more question about service, being of service in the world, but let’s talk about the end of the path and how you in your teachings relate to that.

Sharon: Well, I think it also depends on the orientation or even the lineage or the school. I’ve had Tibetan teachers, for example, who, when they talk about hindrances, those things that can be confusing to us, or masquerading as something else, then they talk about bliss, clarity, and non-thought, that when one enters these states and you think, “I’m done.” But it’s really just a temporary state. And the point is to have a kind of freedom, whatever’s going on, pleasant, painful, neutral. My Burmese teachers would be more, if they were talking about hindrances, they would talk about sleepiness, restlessness, doubt, attachment, aversion, things that …

And so, not every orientation emphasizes the end of the path. Sometimes it’s a little bit like, “Can we talk about something a little more brighter than sleepiness, one more time.” Those were my first teachers. And so, that was very much in there. And so, it’s a mix. I think the most important thing, inner work, as well as outer work, is holding both a vision of possibility and the reality of the next step, both. And we have to do both. Vision of a world without so much greed or hatred or delusion running it. And at the same time, “Okay, this moment, what’s my action?

Thomas: Beautiful. When we look at … because every great tradition, and I think it’s also a remedy, a practice, it’s an expansion of our being, is being of service. And I think we see the degeneration of culture in a more self-centered and more consumerism-based and more like, “What can I get?” more than, “What can I give and how can I contribute?” We see this in the entitlement. “The government should do,” and “They should do,” and, “They should save me,” and, “They should give me … ,” instead of, “What can I contribute, we all together, to the world?” So, I think, with a certain level of maturity of our practice, there is a natural tendency, at least more often, that we want to be of service as well, and participate in the world and give.

But there is a fine line between the traumatized, conditioned, almost compulsion to serve, because it’s hard not to, because all kinds of stuff comes up whenwe don’t, and a more mature soul that has been polished by the practice. And because we are more connected inside to a creative stream, we want to also serve more. And so, maybe you can speak a little to that.

And also how that, because one element of trauma on personal and cultural level is scarcity. It always looks like something’s missing, always something. There’s love missing. As you said, there is a connection missing. There is the resources missing, there’s money missing. But for me, that’s a sign of an underlying traumatization, which is frozen and that creates a scarcity on the surface.

And so, service is in one way how to bring more abundance into scarcity. And so, given your experience and you saw so many people, practitioners, and your own life, so maybe you can talk a bit about the role of service and the wisdom tradition.

Sharon: Yeah. I mean, I think one place to start is really with a kind of introspection, whether you practice mindfulness formally with meditation or not, it’s just becoming aware of your intention, your motivation behind an action and how it feels. There are many, many ways, as you say, of giving a gift.

We can give because we don’t feel we deserve to have anything, so it’s not really generosity. It’s more like martyrdom as we make an offering of our time, of our energy, of a material thing, whatever it is. And then there’s a way of giving that is coming from a greater place of inner sufficiency, your inner abundance. And that can be what’s motivating that. It’s like just a natural thing like, “Well, you’re hungry. Let me try to feed you.” It’s not even thinking. And then there’s a way of understanding our own stress in a moment.

And I’m speaking to you from Barre, Massachusetts, and I also have an apartment in New York City, a small apartment that I rent. So, I was only there for a few days in early March before I left to come up to Massachusetts for what I thought it was going to be two weeks. So, it’s almost six months. And before I left, I was teaching this large group and sitting in the audience before I got up on the stage to speak. And I was sitting next to a person who was extremely anxious. She didn’t know if she should be there. It was a large crowd. There were very confused warnings at that point about COVID and so on. And so, I was just sitting next to her. So I said, “Well, maybe if you try breathing in this way, it’ll help.”

That did not make a dent. And I said, “Let’s talk about love and kindness meditation.” Nothing. And then I said, “Is there anyone you can help?” And she lit up and she said, “I have this elderly neighbor, I can ask her if she needs grocery shopping.” And that was the moment, it was like such a tremendous relief for her. And I thought, “Oh, right. When we’re coming from the right place, it serves us as well as serving somebody else.” And that’s good, that’s okay.

So, having that kind of introspection, remembering that’s an opportunity. Sometimes we feel, “It’s useless, it’s not going to solve climate change if I get my elderly neighbor her groceries.” And there’s so much pain, but we have to do the goodness in front of us, however small it seems. And that will really restore us as well.

Thomas: That’s beautiful. If there is anything you want to leave us with in terms of relating your work to the collective trauma dimension, plus maybe sharing one practice, one thought, one nugget that people can take away from this. I know you also gifted us a meditation, as a bonus gift, that people can listen to, but maybe if there is one nugget of wisdom or one practice that somebody can take into life and practice, anything that seems important to you? And some last thoughts about collective trauma and mindfulness would be lovely.

Sharon: Yeah. Thank you. I think it’s just such a powerful and good time in that there’s this understanding, like with your work. I can remember some years ago somebody who’d attended a retreat, I don’t even know that it was a retreat that I was teaching, but it was a retreat in the school that I participated in. And she said to me, we were just having a conversation, she said to me, in a kind of scolding way, “There’s always trauma in the room. You have to recognize that.” Because it was not recognized, basically.

And if an individual had a particular experience, they maybe either didn’t know it, they didn’t know the roots of their distress or they didn’t choose to disclose it. And the sort of, as you say, collective trauma of a people, with systems of society that are propagating certain myths and an inability to really care for themselves or for one another, it’s grinding. Trauma isn’t, as you know of course, it isn’t always sudden and abrupt.

Really, it can be just this sort of pervasive ongoing stress. I was talking to somebody yesterday, who said that of all that he had been through in his life with some dramatic episodes, the most traumatic thing was growing up in poverty. Just the daily insults or humiliation or injustice. And so, we do carry it as people and I think it’s very important to realize. On the other hand, or as well, we carry incredible capacities for not only healing, but growing and understanding and love and connection and so on.

And in terms of a practice, oddly enough, I have found that sometimes all I need to return to that sense of possibility or remembering what’s intact, what’s not being destroyed, my ability to care, my ability to be present and things that, it’s actually, just pausing. It’s like taking a moment before responding, before pressing send on the email, before just losing it to a reaction. So, it’s like, “Okay, take a breath, just pause, return to yourself and then see.” That’s just what came to my mind when you said that.

Thomas: That’s beautiful. Yeah, I think it’s very powerful because, I think, if we can remember that in the right moment, it’s really fantastic. If there is enough presence to remember that, then it’s lovely and then it’s very powerful. I agree. Sharon, this was really lovely. This is such a lovely quality that you spread around yourself and I feel your deep devotion to your practice and your transmission here in the room. And then, thank you for making the time. And thank you for sharing your wisdom and doing the work that you’re doing. I think you touch many, many people, and you spread pearls of wisdom. And so it’s very lovely. So, thank you very much.

Sharon: Well, thank you. Thank you for your tremendous work and service in the world, it’s inspiring.

Thomas: Thank you.